Saint Therese of the Child Jesus

of the Holy Face

St. Therese's First Communion - Part 3 of "The Little Flower at School," September 30, 2014

The Little Flower’s First Communion

By One of Her Teachers

[Third of a series of four articles. Transcribed from The Far East, May, 1934, pp. 7-10.]

Walk step by step with St. Therese through her First Communion Day in its minutest detail!

To celebrate the feast of St. Therese, and with thanks to the Missionary Society of St. Columban, I present this article about the First Communion of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, written by one of the Benedictine nuns who taught Thérèse.

These articles were commmissioned by The Far East in 1934 to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Thérèse's First Communion (May 8, 1884). We present them in honor of the 130th anniversary of Thérèse's First Communion, which fell on May 8, 2014.

This Month the Golden Jubilee of the First Communion of St. Thérése Is Being Celebrated in Her Old School . . . The Following Reminiscences Have Been Written by a Nun of the Abbey

The dress the 11-year-old Therese Martin, future St. Therese of Lisieux, wore on the day of her First Communion, May 8, 1884

The dress the 11-year-old Therese Martin, future St. Therese of Lisieux, wore on the day of her First Communion, May 8, 1884

III

The day chosen for First Communion was usually the octave of Ascension Thursday. In this year of 1884, however, on account of the illness of Mother Prioress, whose death was feared to be imminent, the chaplain decided to have the ceremony two weeks earlier. It was accordingly set for May 8.

For the previous month the First Communicants were required to become full boarders, so that they might find it more easy to attend Mass every morning and prepare in greater recollection for the coming of Jesus.

Accordingly Thérèse had her little white bed in the dormitory. "Every night," she writes, "the first Mistress [Mother St. Placide] used to come with her little lamp and gently open the curtains of my bed and imprint a tender kiss on my forehead. She showed me so much affection that touched by her goodness I said to her one night: 'Mother, I like you so well that I am going to tell you a great secret.' Then mysteriously drawing forth the precious little book from Carmel [given to her by her sister Pauline three months before the great day] hidden under my pillow, I showed it to her, my eyes alight with joy. She opened it very carefully, looked through it attentively and impressed on me how fortunate I was. Several times, indeed, during my retreat I realized that very few children who like me have lost their mother are treated as affectionately as I was at that age."

As Thérèse, however, was rather delicate and as we knew that she went to Mass in the parish church with her sisters every morning, she was allowed to delay her entrance as full boarder until the closing days. She had a slight cold at the time and the Mother Directress, as a precaution, had her cared for in the pupils’ infirmary. Her sister Celine tells us that she went and spent the recreations with her in intimate, happy talks, full of the thought of the great day now so near; and she gave her one of the pictures in which Thérèse used to delight, that entitled "The Little Flower of the Divine Prisoner," a devotional design very fitting to their joint aspirations.

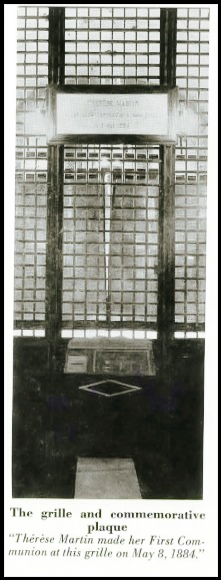

The grille where St. Therese knelt to receive her First Holy Communion at the Benedictine Abbey, May 8, 1884

The grille where St. Therese knelt to receive her First Holy Communion at the Benedictine Abbey, May 8, 1884

From Easter on, the special preparatory catechism classes were given every day. Her earnest attention to these and the little daily sacrifices that the generous child offered to Our Lord made an excellent preparation for the graces of the retreat.

Now let us follow our saintly pupil step by step.

The Retreat

The exercises of the retreat begin on Sunday evening, after compline, at half-past seven. All the boarders attend the opening instruction. This is a favor much appreciated by the older girls, who thus revive sacred memories. Already grace has asserted itself and in the calm and silence of the evening, all go upstairs to the dormitory in a state of unusual recollection.

From this moment every distracting influence is kept out. In the chapel and in the refectory the retreatants are by themselves. Gathered together in a room apart, under the direction of the catechism Mistress, they listen—needlework in hand—to spiritual reading, sing hymns or say the rosary, which they love to have hanging from their belts like the nuns. Thérèse adds (The Story of a Soul, chapter IV): "I was noticeable among my little companions because of the big crucifix which my dear Léonie had given me. I wore it in my belt just as missionaries do, and it was thought that I was trying to copy my Carmelite sister."

The program was interrupted by pleasant recreations and by walks in the orchards, the children singing as they went. Then above all there was the visit to the Blessed Sacrament, and three times a day the touching instructions of Abbé Domin, chaplain to the Abbey, who was so successful in coming down to the level of his young listeners . . . "I listened with great attention to the instructions given by Abbé Domin and I took notes of them carefully," says Thérèse again. And she adds: "How happy I was to be going to the liturgical Office, just like the nuns." This, as a matter of fact, was one of the features of the retreat.

One last walk in silence through the nuns’ garden closed this day of devotion and then, to the strains of a hymn, the retreatants went up to the dormitory.

The Eve of the Great Day

On the eve of the ceremony, following a tradition piously kept up among truly Catholic families, the parents were invited to come to the parlor, that their children might ask their pardon for any trouble they might have given them. Forgiveness likewise was asked from the assembled Mistresses, and Mother Directress gave her beloved children a truly maternal exhortation, in such touching terms that oftentimes the tears flowed silently. A general confession, carefully prepared for, had been made during the previous two weeks, so that the last days might be spent in peace and joy of the soul. Now absolution was received this evening, causing such intense happiness that it sometimes had to be restrained.

The catechism Mistress, Mother St. Francis de Sales, vividly remembers how Thérèse behaved during the retreat. While she was a model of piety, silence and recollection, the joy that filled her heart at the approach of Jesus revealed itself in her overflowing gaiety. We can understand therefore why she exclaims in her autobiography: “Ah, what a blessed retreat that was! I do not think that such joy could be felt anywhere but in religious houses. As the number of children is small, it is all the easier to give special attention to each one. Yes, I say it with a grateful heart: our Mistresses in the Abbey lavished truly maternal care on us. I do not know their reason, but I observed that they watched over me even more attentively than over my companions.”

At length, the longed-for day dawned! What a pleasing sight were the First Communion dresses and veils, hanging in the middle of the dormitory. “Like snowflakes,” is Thérèse’s description of them.

The costume is simple and maidenly: a full, plain frock, with a long muslin veil, a wide silk sash, a pretty cap of fine tulle, reminiscent of that worn at Baptism. There is permission to wear one’s rosary beads at Mass and at Vespers, one’s First Communion medal. No worldly ornament may be worn.

Entering the Chapel

Now let us come into the chapel with our communicants. The shades are lowered; this subdued light, so helpful for recollection, sets off the brightness of the burning candles and of the white dresses. A carpet covers the floor and softens the footfalls. Over the First Communicants’ pews are spread white, fringed tapestries of damask. In front of each child a wax candle on a tall silver candlestick is burning. In the center of the nuns’ choir, the altar for Mary’s month, decked out with flowers and foliage, is ablaze with lights. Little white lamps, to the same number as there are communicants, are slowly burning themselves out at the feet of the Blessed Virgin.

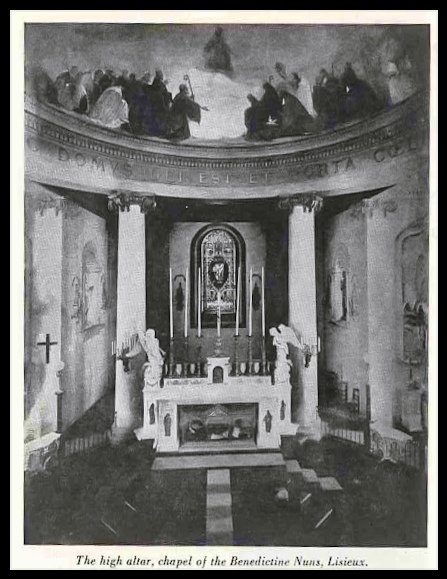

The high altar in the chapel of the Benedictine Abbey of Notre Dame du Pre where St. Therese, the Little Flower, received her First Communion, May 8, 1884

The high altar in the chapel of the Benedictine Abbey of Notre Dame du Pre where St. Therese, the Little Flower, received her First Communion, May 8, 1884

The curtain over the grille is drawn apart, and the parents seated near the altar see, with emotion, their beloved children entering the chapel in procession. From all these youn hearts arise, with touching sweetness, the words of the hymn:

O! saint autel qu’environment les Anges!

Qu’avec transport aujourd’hui je te vois!

Ici, mon Dieu, l’objet de mes louanges

M’offre son Corps pour la premier fois…

[O holy altar where the angels are hovering!

With what transport I see you today!

Here, my God, the object of my praises

Offers himself to me for the first time].*

This is followed by the solemn strains of the Veni Creator, intoned by the celebrant. The Mass is sung by the choir of nuns. At the offertory the children, each holding her candle in her hand, go to make their offering at the grille.

The Mistress of catechism is in charge and everything is done in perfect order without causing any distraction to the communicants. After the elevation an older pupil sings a touching O Salutaris.

The hallowed has come. From the altar, Abbé Domin says a few words which complete the immediate preparation by fanning the flames of desire and love with which these hearts are already burning. He takes as his text that grand verse from St. John’s Gospel (XVII, 10): “All My things are thine…”

The sacristan opens the grille and unfolds the Communion cloth. Through the silence, the priest’s voice is heard: “Ecce Agnus Dei… Domine, non sum dignus…” Then slowly he comes down the steps of the altar, the communicants come forward, kneel one after the other at the Holy Table and receive for the first time the “God Who giveth joy to their youth.” Hallowed, ineffable moment, the memory of which will never die but will pervade a lifetime. Oh, how sweet to the soul of Thérèse was this “first kiss of the Lord!”

As soon as the priest has placed the Sacred Host on the lips of the first child, the choir begins the canticle of thanksgiving “Quid retribuam Domino…”

Thanksgiving

When all have partaken of the Divine Banquet, the singing finishes and the little heads that were bowed in adoration are raised again. Abbé Domin repeats his text, applying it now to the gratitude with which his listeners’ souls are filled; he urges them to pray for their parents and benefactors, and then the Holy Sacrifice is concluded.

During the thanksgiving, the voice of a former pupil is heard singing:

Il est à moi, Celui que le ciel même

Que l’universe ne saurait contenir;

Il est à moi, je l’embrasse, je l’aime.

Rien ici-bas ne peut nous désunir…

[He is in me, the One whom even heaven,

Even the universe cannot contain;

He is in me; I embrace Him; I love Him;

Nothing here below can separate us].*

But what does the sweetest music matter when Jesus Himself speaks in the depths of the soul? From the greater number He asks only love and fidelity. To some privileged souls He already gives glimpses of the heights of perfection. From the lips of the saintly child herself let us hear what He said to Thérèse.

“It was the embrace of love! I felt that I was loved and I said in return: ‘I love You, and I give myself to You for ever.’ Jesus asked nothing of me, He sought no sacrifice. For a long time now He and little Thérèse had known and understood each other… On this day our meeting could not be called a mere meeting but rather a fusion. We were no longer two. Thérèse had disappeared like the drop of water that is swallowed up in the midst of the ocean. Jesus alone remained. He was Master and King.

“Had not Thérèse asked him to take over her liberty from her? This liberty frightened her; she felt herself to be so weak and frail that she wanted to be united for ever to Divine Strength.

“Her joy now became so great, so deep, that she could not hold it in. Soon tears of happiness poured down her cheeks, to the great surprise of her companions who kept saying to one another later on: ‘Why did she cry? Had she something on her conscience?... No, it was because she did not have her mother with her, or her sister the Carmelite, of whom she is so fond.’ And nobody understood that when all the joy of Heaven comes into a heart, this heart- exiled, weak and mortal- cannot endure it without weeping” (The Story of a Soul, chapter IV.)

After the thanksgiving the happy communicants went to the large community parlor to embrace their relatives and friends. The meeting was brief, as this was not a time for long conversation. Thérèse’s countenance still bore traces of the deep emotion that she had just experienced. We have evidence of this in the following little incident told by a girl who was related to the Guérins.

“My mother remarked that the child had been weeping. ‘That poor little girl’s eyes are red,’ she said to M. Guérin [uncle of Thérèse].

“The uncle did not seem surprised. He just replied: ‘She has a slight cold,’ wishing no doubt to save his dear little Thérèse from embarrassment, for he knew her tender piety. Afterwards, on reading the Story of a Soul, I readily understood the reason for those tears.”

Memories of Onlookers

The following are some reminiscences written by the nuns and older pupils who were present at that memorable First Communion.

“On the day of her First Communion, Thérèse looked more like an angel than a human being. A radiant heavenly fervor was noticeable in her eyes and in her bearing. I observed this every time she received the Blessed Sacrament; her features seemed to reflect the depth of her faith and the ardor of her love.” These are Mother Prioress’ words.

Let us hear the Mistress of catechism again: “To prepare for her First Communion Thérèse made acts of virtue over a very long period. She called them ‘flowers to decorate Jesus’ resting-place’ and she wanted them to be many and fragrant. Beneath this simple, childlike mode of preparation lay genuine, tender love. From this time on, she kept the silence more faithfully than ever and was still more deeply pious.”

A novice who was afterwards to be her teacher writes: “On the day of her First Communion I took delight in gazing on this angel of piety and innocence… After Mass, as I came towards the little communicant, an indefinable feeling of respect overcame me; she seemed to me to be streaming with grace. Putting my arm around her so that our two white veils became as one, I said: ‘You are very happy, Thérèse?’ ‘Oh, yes, I am,’ she replied, and the light in her eyes and her tone of voice revealed the immensity of her happiness.”

A Child’s Prayer

Sister Henriette, a lay-Sister who died in 1917, has left us these interesting details.

“I was changed from the school at Easter, 1884, but I was called on to help in the refectory on the First Communion day. This gave me the pleasure of seeing Thérèse more closely. She came to lunch at two o’clock with her companions. One little girl said to me: ‘If you only knew, Sister, what she asked Our Lord during her thanksgiving…. To die, Sister! Wouldn’t that make you afraid?’

“But Thérèse just looked at them as though she pitied them, without saying anything. Then I answered, saying: ‘You don’t understand. Thérèse, like her holy patroness, asked to die of love.’

“Then she came to me and looked into my eyes. ‘You understand, Sister,’ she said. ‘They don’t.’”

The day was spent in the calm of the monastery. After dinner there was a quiet period of recreation during which the First Communicants gave souvenir cards to the Mistresses and to their companions; then there was a short visit to the Blessed Sacrament. Thus the great event of the morning was kept uppermost in their minds until the time for Vespers, when they made their solemn promises of loyalty to Jesus.

Renewing Baptismal Vows

Half-past two comes. The white procession starts for the chapel again. At the foot of the altar a credence table is placed and on it are the crucifix and the book of the Holy Gospels, with candles all around. After Vespers has been sung, a procession is formed. In front is the banner of the Children of Mary; and the youngest pupils feel very proud and happy to be holding the golden streamers of the banner. The vibrant strains of the time-honored hymn are heard: “Quand l’eau sainte du baptême….”

Passing the grille, the procession proceeds into the sanctuary and the communicants stand before the credence table. One of them pronounces the renewal of the baptismal promises, and then her companions, each having her right hand on the sacred book, repeat two by two the solemn pledge: “I renounce Satan…. I give myself to Jesus Christ for ever.”

Continuing on its way, the procession goes around the sanctuary and reenters the enclosed part of the chapel to the chanting of the psalm “In exitu,” the first verse of which is repeated as a refrain by those present. The children now resume their places to listen to the words of the preacher inviting them on the evening of this great day to throw themselves into the arms of their heavenly Mother.

Consecration to Mary

Once more the procession is formed; this time – while the older pupils sing a hymn to Our Lady – the First Communicants are ranged together in a half-circle at the feet of the Mother of God.

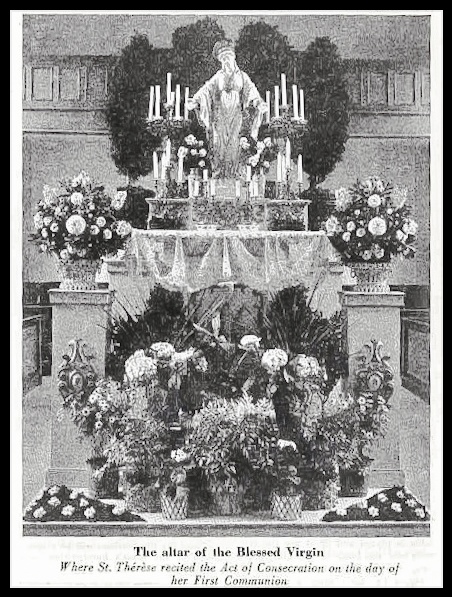

The altar of the Blessed Virgin, decorated for a First Communion, where St. Therese recited the Act of Consecration to the Blessed Virgin in the name of her classmates on the afternoon of her First Communion day, May 8, 1884

The altar of the Blessed Virgin, decorated for a First Communion, where St. Therese recited the Act of Consecration to the Blessed Virgin in the name of her classmates on the afternoon of her First Communion day, May 8, 1884

All kneel down, and the childlike voices begin a tender, beseeching hymn. At its close the girl appointed to recite the act of Consecration to the Blessed Virgin rises and goes to kneel close to the step of the altar. When there is an orphan among the communicants, this honor is always reserved for her. Accordingly, this year it was Thérèse Martin [because her mother was dead]… and with what sentiments of trustful, filial piety she recited this act in the name of her companions. Once more let us open the Story of a Soul: “I put my whole heart into my consecration to the Blessed Virgin and into my prayer that she might watch over me. I think that she looked down with love on her little flower and smiled once more upon her. I recalled her visible smile that had previously healed and saved me; I well knew what I owed to her. Had not she herself, on the morning of this eighth of May, placed within my soul her Jesus, ‘the Flower of the fields and the Lily of the valleys’?”

Deeply moved and silent, those present listen to the Act of Consecration. The scene is a beautiful one and it touches the onlookers to tears.

After another hymn the First Communicants go back to their places for solemn Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, which closes this heavenly day.

The children then rejoin their families; the rejoicings of the home circle must have their turn.

Thérèse has written: “I was not indifferent to the family feast that was prepared at Les Buissonets. My happiness, however, was peaceful; nothing could disturb my interior joy.” How could the pretty dress and the presents captivate her young heart? No, this heart of hers had found too much joy in Jesus to take pleasure in earthly satisfactions. It longed for the day of “the eternal Communion in our true home, the day that will know no decline.”

Mass of Thanksgiving

The First Communicants were to return in the evening to the Abbey in order to be present on the following morning at the Mass of thanksgiving, which was always early. Thérèse, by special permission, did not return that evening but she was there in good time the next morning.

After the Mass of thanksgiving, the chaplain gave a short discourse, the theme of which was always gratitude and perseverance. Afterwards he received the children and their friends, who thanked him for the devoted care with which he had prepared their young souls for the first visit of Our Lord. At this time he gave out the First Communion certificates and a souvenir picture.

The children were permitted to spend several days at home. Each family was happy to have its little First Communicant, whose presence, after such great graces, would draw down upon the home the blessings of Heaven and would diffuse the fragrant influence of Jesus.

A commemorative plaque has been set at the exact place where on May 8, 1884, the sacramental union of Jesus and little Thérèse Martin took place.

|

Our June Issue will present the fourth and last in this series of articles written by a Benedictine nun, who taught St. Thérèse. Next month’s article will include some interesting personal recollections and among the illustrations will be a specimen of the saint’s handwriting as a child. |

Among the glories of the Abbey is not this one of the grandest and most enviable – the possession of that hallowed place where the first meeting between Jesus and the greatest saint of modern times befell, where an incalculable impetus was given to a spiritual life that is today a powerful influence all over the world?

__________________

* translations by Maureen O'Riordan

This article originally appeared in the May 1934 issue of The Far East (U.S.A. edition).

- See an image of "The Little Flower's First Communion (Part 3)," exactly as it appeared in The Far East in May 1934.

- It is reprinted by “Saint Therese of Lisieux: A Gateway” with permission from the Missionary Society of St. Columban at www.columban.org You may read it online at www.thereseoflisieux.org/abbey3. Permission is granted to duplicate this article in whole; please include this notice of acknowledgement.

- To learn more about the Columban Missions, or to send a thank-offering, please visit

- in the United States, www.columban.org

- in Ireland, www.columban.com; and

- in the United Kingdom, www.columbans.co.uk

Special thanks to Linda Smith, who typed this article for publication; to her husband, Scott Smith, who formatted the print-friendly version you may download; and to Patricia Taussig, who prepared the illustrations and the image of the original May 1934 article for publication. Please pray for these generous partners in the apostolate.

Look out in a few weeks for the fourth and last article, which concludes the account of Therese's school days.

Help Wanted

- Read about how I discovered "The Little Flower at School" articles in 2014. I found these articles just by searching the Internet and following the clue there, and I am confident that many other such treasures await discovery. If you want to help find them, please e-mail me. Thank you.

More gifts

Virtual Choir of Discalced Carmelite Nuns Singing for the 500th Anniversary of the Birth of St. Teresa of Avila

This "virtual choir" of Discalced Carmelite nuns from around the world singing in honor of the 500th anniversary of the birth of St. Teresa of Avila evokes most beautifully the desire of St. Therese "to preach the gospel on all five continents simultaneously." They are chanting a poem often called "St. Teresa's bookmark," also known as "The Efficacy of Patience." The text in Spanish:

"Eficacia de la Paciencia"

Nada te turbe,

nada te espante,

todo se pasa,

Dios no se muda;

la paciencia

todo lo alcanza;

quien a Dios tiene

nada le falta:

Sólo Dios basta.

English translation:

"Efficacy of Patience."

Let nothing trouble you,

Let nothing scare you,

All is fleeting,

God alone is unchanging.

Patience

Everything obtains.

Who possesses God

Nothing wants.

God alone suffices.

[from The Collected Works of St. Teresa of Avila, Volume Three: translated by Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D. and Otiliio Rodriguez, O.C.D. Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, Inc., 1985].

"St. Therese of Lisieux at School, Part 2" - the second of four articles written in 1934 by a Benedictine nun who taught Therese

St. Therese in 1883, at age ten, represented in her school uniform

St. Therese in 1883, at age ten, represented in her school uniformThe Little Flower at School

By One of Her Teachers

Further Memories of St. Thérèse as a Pupil of the Benedictine Nuns in Lisieux . . .

Written for The Far East by a Member of the Community

Second of a series of four articles. Transcribed from The Far East, April, 1934, pp. 7-9.

With thanks to the Missionary Society of St. Columban, I present this second of a series of four articles about the school life and First Communion of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, written by one of the Benedictine nuns who taught Thérèse. These articles were commmissioned by "The Fast East" in 1934 to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Thérèse's First Communion (May 8, 1884). We present them in honor of the 130th anniversary of Thérèse's First Communion; the anniversary fell on May 8, 2014.

This second article discusses Therese's academic strengths and weaknesses; the older student who resented her; the morning schedule of the Abbey school; recreation; the daily visit to the Eucharist; Therese's catechism class; and the anticipation of her First Communion. This article leaves Therese in the autumn of 1883, when she was ten years old.

II

Class Work

Thérèse never wore the red belt and had the green for only one year. Thanks to the attentive care of her “Little Mother” [her sister, Pauline], our new pupil was in no way backward. Does she not also say in her autobiography that from the beginning success fell to her, bringing encouragement and rejoicing? Our industrious pupil held this gain of a year until she left the school. She was intelligent and fond of study, but her spirit of faith was too strong to let her take things easily just because the Lord had endowed her with natural gifts. Thérèse brought a serious and sustained application to her work. The high marks and first places she won in the weekly tests were the reward of her diligence. Undoubtedly she had to strive hard to withstand the competition of classmates who were older than she and not less gifted nor less studious.

It would be a great mistake to think that these tears of Thérèse came from self-love or ambition. She fancied that God would be less pleased with her and that she would grieve her good father, who manifested a certain disappointment when her marks went as low as 3 (out of 6) and, on the other hand, seemed so happy when his daughters brought him reports showing high marks and first places. The day-boarders could bring work with them to do at home in the evenings. M. Martin and the older girls took the greatest interest in the studies and progress of the children. The truth is, the, that the tears shed by Thérèse came from her delicacy of conscience and her extreme goodness of heart.

Petty Persecution

In outlining briefly the day of a pupil at the Abbey of Notre Dame du Pré, we shall follow little Thérèse step by step.

Eucharistic Visit

Little Thérèse never failed to throw down whatever she held in her hand as soon as the mistress would approach the different groups and say: “It is time to go to chapel.” And her example would bring along others who were dallying hesitantly.

Pupils at the Abbey at outdoor recreation in 1885, when Therese, 12, was a student there

Pupils at the Abbey at outdoor recreation in 1885, when Therese, 12, was a student there Pupils of the Benedictine Abbey, wearing school uniforms, at recreation on the terrace, overlooking the town of Lisieux

Pupils of the Benedictine Abbey, wearing school uniforms, at recreation on the terrace, overlooking the town of LisieuxRecreation, in bad weather, was spent on the terrace, which was spacious and had a southern exposure.

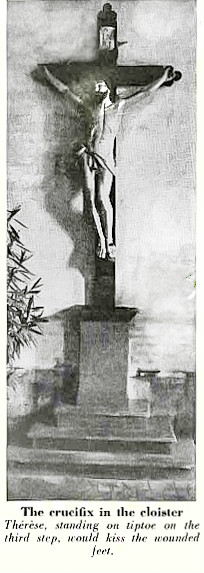

The crucifix that stood in the cloister of the Benedictine Abbey. Therese stood on tiptoe on the third step to kiss the representation of the wounded feet of Christ.

The crucifix that stood in the cloister of the Benedictine Abbey. Therese stood on tiptoe on the third step to kiss the representation of the wounded feet of Christ.In Religion Class

The chaplain bore witness, not without pride, that at the customary examination he had deliberately tried to puzzle Thérèse but that he had not succeeded. So he called her his “little Doctor of Theology” and one can foresee perhaps that these words may soon be shown to have been prophetic. [Note of 2014: This sentence reflects that in the 1930s talk of Therese as a Doctor of the Church had begun].

Trials and a Great Favor

When the school reopened in October, Thérèse continued to be the simple, frank schoolgirl of old, but she was more and more edifying. For was not this to be for her the great year. A few months more and the longed-for day would dawn!

This article originally appeared in the April 1934 issue of The Far East (U.S.A. edition).

- See an image of "The Little Flower at School, Part 2" exactly as it appeared in The Far East in April 1934.

- It is reprinted by “Saint Therese of Lisieux: A Gateway” with permission from the Missionary Society of St. Columban at www.columban.org You may read it online at www.thereseoflisieux.org/abbey2. Permission is granted to duplicate this article in whole; please include this notice of acknowledgement.

- To learn more about the Columban Missions, or to send a thank-offering, please visit

- in the United States, www.columban.org

- in Ireland, www.columban.com; and

- in the United Kingdom, www.columbans.co.uk

Special thanks to Linda Smith, who typed this article for publication; to her husband, Scott Smith, who formatted the print-friendly version you may download; and to Patricia Taussig, who prepared the illustrations and the images of the original April 1934 article for publication. Please pray in thanksgiving for our generous and expert volunteers.

The next article, part 3 of four, gives a step-by-step description of every detail of St. Therese's First Communion Day, telling much about the ceremony and the day that Therese did not record in Story of a Soul. Please God, I will be able to upload it for the special gift for St. Therese's feast on Wednesday, October 1, 2014. Please check back.

Help Wanted

- Read about how I discovered "The Little Flower at School" articles in 2014. I found these articles just by searching the Internet and following the clue there, and I am confident that many other such treasures await discovery. If you want to help find them, please e-mail me. Thank you.

More gifts

Pray in the choir of the Carmel of Lisieux with the Carmelite nuns and with St. Therese, September 20, 2014

The Carmelites of Lisieux at prayer in the choir where St. Therese prayed. Click on the image to make a virtual visit to this choir.

The Carmelites of Lisieux at prayer in the choir where St. Therese prayed. Click on the image to make a virtual visit to this choir.

The Carmelites of Lisieux invite you to make a "virtual visit" to the choir where St. Therese and the Carmelites of her day prayed the Divine Office, made their mental prayer, and attended Mass every day. Join the Lisieux Carmelites in prayer at this 3:20 film on Vimeo, or make the English "pilgrimage visit" they offer on the Web site of the "Carmel de Lisieux." An audio in English gives the words of St. Therese about prayer.

As soon as the 15-year-old St. Therese entered the enclosure on April 9, 1888, as she writes, "I was led, as are all postulants, to the choir, and what struck me were the eyes of our holy Mother Genevieve, which were fixed on me." It was here that she received the Habit on January 10, 1889 and, after her profession, received the black veil on September 24, 1890.

The professed nuns participated in the Divine Office from their "stalls" against the wall. At the time of Therese, at least some of them made the morning and evening hour of mental prayer" while sitting "on their heels" on the floor of the choir. Sister Marie of the Trinity remembers that Therese, who never got enough sleep, often fell asleep during the hour of mental prayer or the thanksgiving after Holy Communion; her head fell over and she slept, her forehead touching the floor.

It was also here that, at evening prayer, Therese was placed in front of Sister Marie of Jesus, who spent the whole hour unconsciously tapping her teeth with a fingernail. Read Therese's humorous account of how "I paid close attention so as to hear it well, and my prayer, which was not the Prayer of Quiet, was spent in offering this concert to Jesus."

In the early summer of 1897, Therese was so sick that she had to give up attending the choir. But on August 30, 1897, she was placed on a movable bed and wheeled down the cloister from the infirmary to the entrance to the choir, where "she prayed for some time with her eyes fixed on the Blessed Sacrament. We photographed her before bringing her in." See the August 30, 1897 photograph of St. Therese.

From this choir Therese's Carmelite sisters participated in her funeral Mass on October 4, 1897, and it was here, on March 26, 1923, that they welcomed their sister's body back after the solemn translation of her relics from her grave in the municipal cemetery at Lisieux to the chapel of the Carmel.

We congratulate the "Association les amis de Sainte Therese de Lisieux et de son Carmel" and the Carmelites of Lisieux for producing this beautiful film and for making it available in English.

St. Therese's sister Celine entered the Carmel of Lisieux 120 years ago today, on September 14, 1894

"Celine. Sister and Witness of St. Therese of the Child Jesus," by Stephane-Joseph Piat. The cover shows Celine, left, at twelve; Therese, right, at eight, 1881.

"Celine. Sister and Witness of St. Therese of the Child Jesus," by Stephane-Joseph Piat. The cover shows Celine, left, at twelve; Therese, right, at eight, 1881.

120 years ago today, on September 14, 1894, Therese's sister Celine entered the Carmel of Lisieux at the age of 25. She had taken care of her father until his death six weeks before, on July 29, 1894.

Celine's story is told in the book Celine: Sister and Witness of St. Therese of the Child Jesus by a Franciscan priest, Stephane-Joseph Piat, who knew her well in her later years. (She died on February 25, 1959, at the age of 89). She herself tells the story of the three years she spent with Therese in Lisieux Carmel in her memoir My Sister Saint Therese, first published in French in the 1950s.

Celine had lived much longer "in the world" than her sisters. From the age of seventeen she had been in charge at Les Buisonnets. She had accompanied her father during his confinement in a mental hospital; nursed him, together with Leonie, and managed his household after his release; participated in the social life of the family of her uncle Guerin; refused two proposals of marriage; considered joining the Jesuit Father Almire Pichon in an apostolate in Canada; been an active member of her parish; organized other young women in charitable and apostolic works in Lisieux; and vigorously pursued studies in art, photography, and other fields. Because she had looked after her father and managed his household, and because of her strong personality, incredible energy, and many talents, Celine's early adjustment to the Carmelite way of life, which at that time was so rigid (for a guide to all its minute customs, see the "Paper of exactions" at the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux) was a challenge. Like so many of us do, she often compared herself with Therese and became discouraged despite her courageous efforts.

Read her eyewitness testimony about Therese at the 1910 diocesan process in the book St. Therese of Lisieux by those who knew her at

At the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, read the circular of Sister Genevieve of the Holy Face, an account of her life which was prepared at Lisieux and sent to other Carmels at Celine's death.

Read an online biography of Celine on the Web site "Martin Sisters."

September 14, 1894 was an historic date in Carmel not only because of the entrance of the young woman who would give us such valuable testimony about her sister-saint but also for several other reasons:

To make room for Celine, the cells were moved around, and it was to prepare for September 14 that Therese moved into her last cell, which she occupied from then until she left it for the infirmary on July 8, 1897

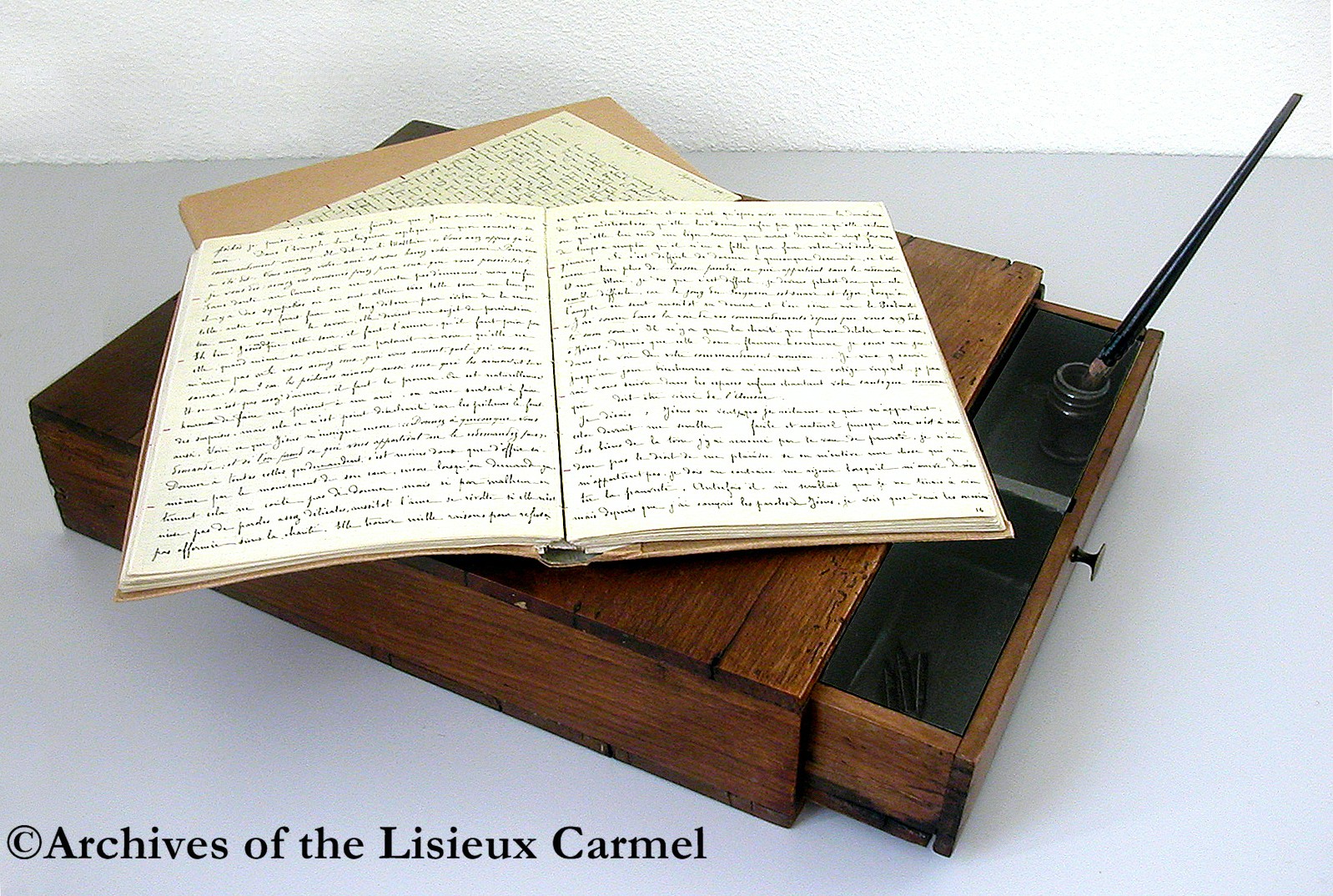

writing-desk on which St. Therese wrote the three manuscripts of "Story of a Soul"

writing-desk on which St. Therese wrote the three manuscripts of "Story of a Soul"

When Celine entered, Therese passed on to Celine the ecritoire (small wooden writing-desk held on one's lap) that she herself had been using. Therese replaced it with another, no longer fit for use, which she had found in the attic. So it's on this last, somewhat battered writing-desk, which was displayed in the United States in the summer of 2013, that Therese wrote the three manuscripts of "Story of a Soul"

and all her letters to her spiritual brothers, the young priest Adolphe Roulland and the young seminarian Maurice Belliere.

Celine brought with her a small notebook in which she had copied out extracts from her uncle's Bible. She passed this notebook on to Therese. Since the nuns did not have Bibles, some of the passages were new to Therese. It was in this notebook that Therese found the Scripture passages that were the foundation of her "way of confidence and love": "If anyone is little, let that one come to me." "For to the one that is little, mercy will be shown." "You shall be carried on the knees and fondled at the lap."

Celine also brought that day another object that would be important to the spread of Therese's message: the photographic apparatus with which most of the photographs of Therese as a Carmelite were taken.

May Celine (Sister Genevieve of the Holy Face) obtain for us the grace to enter into following her sister's way of confidence and love with the same energy and courage with which she entered Carmel.