Saint Therese of the Child Jesus

of the Holy Face

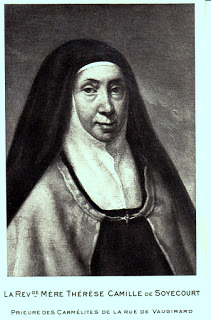

Entries in Mother Camille de Soyecourt (1)

Saint Therese of Lisieux and the Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne," July

St. Thérèse of Lisieux

and the Martyred Carmelites of Compiègne

Stained-glass window in the Church of Saint-Honoré d'Eylau depicting the martyrdomof the Carmelite nuns of Compiegne, by Félix Gaudin based on a card by Raphaël Freida.

GFreihalter / CC BY-SA

On July 17, 1794, sixteen nuns of the Carmel of Compiègne (the whole community, except three who were away at the time of the arrest) were guillotined in Paris. They had offered their lives for God’s peace in the world and for those in prison, and they went to their deaths as to a wedding, chanting of God's mercy. Ten days after their execution, the Reign of Terror ended. Read their story online in Wikipedia or read To Quell the Terror: The True Story of the Carmelite Martyrs of Compiègne.[1] In this article I explore little-known facts about the bond between the Carmel of Lisieux and that of Compiègne and the influence of the martyrs on St. Thérèse.

1835-1838: Refounding the Carmel of Compiègne and Founding the Lisieux Carmel

Mother Camille de SoyecourtA short-lived attempt to restore the Carmel of Compiègne began in 1835, led by the tireless Mother Camille de Soyecourt of the Carmel of the rue de Vaugirard in Paris. After the French Revolution, Mother Camille did much to bring about the rebirth of Carmel in France. Compiègne is in the province of Picardy. Because Mother Camille had contributed nuns for the refoundation of Compiègne, she was one of six Carmelite prioresses who had to refuse to send nuns for a new monastery in Lisieux. Fr. Nicholas Sauvage, the priest who was to establish the Carmelite foundation in Lisieux, had several young candidates and was searching for experienced nuns (“foundresses”) to join them. He wrote to Mother Camille de Soyecourt, who answered about January 1837 that she had furnished nuns for the refounding of Compiègne and had no other sisters to spare.[2] (The Carmel of Poitiers opened its doors to Père Sauvage’s candidates. In 1838, when they were ready to make their vows, Poitiers sent the foundresses, including Mother Genevieve of St. Thérèse, with whom St. Thérèse lived for almost four years, with the new nuns to found the first Carmel of Lisieux).[3]

Mother Camille de SoyecourtA short-lived attempt to restore the Carmel of Compiègne began in 1835, led by the tireless Mother Camille de Soyecourt of the Carmel of the rue de Vaugirard in Paris. After the French Revolution, Mother Camille did much to bring about the rebirth of Carmel in France. Compiègne is in the province of Picardy. Because Mother Camille had contributed nuns for the refoundation of Compiègne, she was one of six Carmelite prioresses who had to refuse to send nuns for a new monastery in Lisieux. Fr. Nicholas Sauvage, the priest who was to establish the Carmelite foundation in Lisieux, had several young candidates and was searching for experienced nuns (“foundresses”) to join them. He wrote to Mother Camille de Soyecourt, who answered about January 1837 that she had furnished nuns for the refounding of Compiègne and had no other sisters to spare.[2] (The Carmel of Poitiers opened its doors to Père Sauvage’s candidates. In 1838, when they were ready to make their vows, Poitiers sent the foundresses, including Mother Genevieve of St. Thérèse, with whom St. Thérèse lived for almost four years, with the new nuns to found the first Carmel of Lisieux).[3]

That first refounding of the Compiègne Carmel was short-lived. During the revolution of 1848, the nuns had to return to their Carmels of origin. In 1866 nuns from Troyes settled in a temporary house in Compiègne; the monastery was completed in 1872, and the chapel inaugurated in 1888, the year Thérèse entered the Carmel of Lisieux. In 1992 the Carmelites of Compiègne moved to the nearby village of Jonquières.[4]

1870-1871: Sister Fébronie of the Holy Childhood, a Carmelite of Lisieux, lived with the Carmelites of Compiègne

Sister Fébronie (1820-1892) entered the Lisieux Carmel on January 15, 1842. Due to the exigencies of the Franco-Prussian war, she spent several months in 1870-1871 with the Carmelite nuns of Compiègne in Rennes. The war threw Normandy into a panic. The families of some nuns asked to take their daughters home to keep them safe. Three nuns, including Sister Fébronie, left Lisieux at the end of September 1870; four others, including St. Thérèse’s future prioress, Marie de Gonzague, left in January 1871.[4a] Sister Fébronie declined her father’s offer of shelter in his home in Rennes. Instead, no doubt to continue her Carmelite life, she sought refuge at the Carmel of Rennes, which had already taken in all the Carmelites of Compiègne. At the end of January 1871 the armistice was signed, and by March 19, 1871, the seven nuns who had fled had returned to Lisieux.[5] Sister Fébronie always maintained a lively friendship with the nuns of Compiègne. She was subprioress when she died in the flu epidemic on January 4, 1892,5a and Thérèse, who had worked with her for several years, assisted her in her last moments. Her prioress, Mother Agnes, wrote in her death notice:

Many times in letters she left, we could see how she edified one of our dear Carmels intimately united with ours, where in a particular situation she had spent several months. Learning of her sudden death a few weeks ago, we received from the Reverend Mother Prioress a new proof of a good remembrance that they have of her in that beloved Community.[6]

The Carmel “intimately united with ours” could have been Rennes, but it seems much more likely to have been Compiègne. Later, on April 23, 1896, Mother Marie de Gonzague wrote to the prioress of Compiègne

… I do not need to remind you, Mother, of our fraternal union. You know how strongly it is cemented by our dear Sister Fébronie, who is and will be remembered so reverently by present and future generations.[7]

1888: The origin of the religious name of Sr. Thérèse of St. Augustine of Lisieux

When Thérèse Martin entered in April 1888, her life was touched by a nun whose religious name derived from that of Madame Lidoine, the martyred prioress of the Compiègne Carmel, known in religion as Mother Thérèse of St. Augustine. (The feast of the blessed martyrs is listed as “Blessed Teresa of St. Augustine and companions, martyrs”). Madame Lidoine, in turn, had been named for the first Mother Thérèse of St. Augustine, “Madame Louise,” a princess of France, the daughter of King Louis XV, who entered the Carmel of Saint-Denis in 1770. On June 19, 1873, when Thérèse Martin was five months old, the decree for the introduction of Madame Louise's cause for sainthood was issued. [8]

Sister Thérèse of St. Augustine of Lisieux was the nun whom St. Thérèse said “had the faculty of displeasing me in everything.”

1894: The two Thérèses help to decorate the chapel of Compiègne for the centenary of the martyrdom

The centenary of the martyrdom, which fell on July 17, 1894, led to much excitement in the French Carmels and to a shift in public opinion about the Carmelites of Compiègne. For this occasion the Carmel of Compiègne had asked all the Carmels in France to help them decorate their chapel. No doubt because of her religious name, Sister Thérèse of St. Augustine was assigned to work with the future Saint Thérèse on this project. In Thérèse’s diocesan process Sister Thérèse of St. Augustine testified;

I witnessed the zeal, the devotion that she demonstrated on this occasion. She couldn’t contain herself for joy, and said “How happy we would be if we could have the same fate! What a grace that would be!”[9]

A photo of the chapel at Compiègne on this occasion appears in Sainte Thérèse de Lisieux: La vie en images.[10] The banners created by the Lisieux Carmel are seen in the nave.

In 1896, the Lisieux Carmel prays successfully to the Carmelite martyrs of Compiègne for healings that might advance the beatification

The cause of the Carmelite martyrs of Compiègne was very much “current news” in the time of St. Thérèse, and the Carmel of Lisieux was fervently devoted to the martyrs and eager to assist their cause. The cause was opened at the diocesan level in 1896. This probably happened early in the year, for on April 23, 1896, Mother Marie de Gonzague wrote to the prioress of the Carmel of Compiègne to report two healings that had taken place after the Carmelites of Lisieux had prayed to “our Holy Martyrs.” Each concerned a blood relative of a Carmelite of Lisieux. The first sick man was a dying captain, the father of three young children. He was the cousin of Mother Marie of the Angels, Thérèse’s novice mistress; he had had no hope of recovery. After the nuns prayed to the martyrs of Compiègne and to the Blessed Virgin, he was cured. The second was a young girl in England, the niece of one of the Lisieux Carmelites, who was in terrible pain after an operation on her foot. After the Carmelites prayed to the martyrs of Compiègne, she was able to walk again. The letter suggests that the Carmelites of Lisieux had asked for a novena, perhaps a novena of Masses, at Compiègne and that Mother Gonzague is sending an offering for it.[11]

Read Mother Gonzague’s letter to the prioress of the Compiègne Carmel at the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, with thanks to the Internet Archive. [12]

September 1896 - Msgr Roger de Teil, Vice-Postulator for the Carmelites of Compiègne and Thérèse’s future vice-postulator, speaks to the Carmelites of Lisieux about the cause of the martyrs

Early in September 1896 (before September 7th), Msgr Roger de Teil, who had been appointed vice-postulator for the cause of the martyrs and was touring the French Carmels, arrived at Lisieux to speak and to ask the nuns to pray that a miracle might be worked at the intercession of their martyred sisters to permit their beatification. He addressed the community in the speakroom

Shortly after the death of Msgr. de Teil in 1922, Thérèse’s sister Pauline, Mother Agnes of Jesus, recalls his presentation and her sister’s reaction:

Even during the lifetime of our Venerable, Mgr de Teil entered into relations with our Carmel. Then he gathered together all the necessary documents for the Process of our Blessed Martyrs of Compiègne and delivered an enthusiastic conference to the community. In leaving the speakroom, Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus said to us, very much edified, “Isn’t he touching and zealous, the Postulator! How one would wish to be able to report to him miracles worked by our Martyrs of whom he speaks with such great affection.”[13]

Thérèse is said to have remarked that, with such a vice-postulator, the Carmelites of Compiègne would surely be raised to the altars soon.[14] How could she have guessed that Msgr de Teil would be appointed vice-postulator for her own cause and that she would be canonized first? (The cause of the blessed martyrs was recently advanced by Pope Francis)[14a] During his conference Msgr de Teil said “If any of you who are listening to me have the intention of being canonized, please have pity on the poor vice-postulator and work plenty of miracles!” . . . . Msgr. de Teil’s comment, years later, was “Soeur Thérèse, obedient child, did precisely as she was told.”[15] In 1899 Msgr de Teil would read Thérèse’s Story of a Soul and speak very favorably of it.[16]

In 1909, at the request of Mother Marie-Ange of the Child Jesus, then prioress of Carmel, Bishop Lemonnier appointed Msgr. de Teil, a distinguished canon lawyer who was then a canon of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, as vice-postulator for the cause of Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus. (He was also postulator for Madame Louise of France, for the martyrs of September 1894, and for Pius IX).[17] He shepherded Thérèse’s cause until his death just a year before she was beatified.

September 1896: The Carmelite community at Lisieux offers novenas to the martyrs of Compiègne and seeks a relic for the cure of their Sister Marie-Antoinette

A few days later, at the request of Mother Gonzague, Mother Marie of the Angels, Thérèse’s novice mistress, wrote to the prioress of Compiègne asking for “a little relic of our holy Mother Martyrs” to place on the body of Sister Marie-Antoinette, a young turn-sister who was dying of tuberculosis. She had returned from Lourdes without a cure “and is nothing but a walking skeleton.” The Carmelites were “trying a second novena to our Mother Martyrs” and “having a novena of Masses said so that her miraculous healing might favour the beatification of our holy Mothers.” Mother Marie of the Angels writes “we recently heard Father de Teil, who informed us of his progress, his desires. How happy we would be if the miracle we are soliciting could recompense his zeal and dedication.”[18]

Read the letter of Mother Marie of the Angels to the prioress of Compiègne at the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux.

Sister Marie Antoinette was not cured; she died November 4, 1896.

These martyrs of the French Revolution would naturally have appealed to Thérèse, the granddaughter of two soldiers of Napoleon. But Msgr. de Teil’s visit stimulated her devotion to the Carmelites of Compiègne. “After that date, she had for these martyrs a great veneration.”[19] Her encounter with Msgr. de Teil reactivated in Thérèse what she wrote a few days later to Marie of the Sacred Heart in her famous “Manuscript B:” “Martyrdom was the dream of my youth, and this dream has grown with me within Carmel’s cloisters.”

Saint Thérèse treasured images of the Carmelites of Compiègne

Saint Thérèse kept three holy cards with images of the Carmelite martyrs of Compiègne. In her breviary she kept a holy card made from a photograph of a tableau painted a little before the centenary in 1894 by Mother Marie of Jesus of Leindre [sic], a Carmelite of Compiègne.[20] View Thérèse’s holy card of the Carmelite martyrs of Compiègne.

The painting is now at Jonquières, where the Carmelites of Compiègne moved in 1992.[21]

Thérèse had two copies of the other holy card, which listed the name of each nun and her place of birth, with a short account of their martyrdom and a prayer for their beatification. I believe that this card was probably distributed in 1896 when the cause was opened. This image accompanied Thérèse to the infirmary in July 1897. She placed it in her little “book of graces at the table," which was constantly by her. She kept the second image, which was exactly the same, in the volume of John of the Cross she had in the infirmary (the Spiritual Canticle followed by the Living Flame of Love).[22] That these images accompanied her into the little infirmary where she died confirms that her devotion to these martyrs, made stronger in September 1896, remained fervent until her death a year later.

See the image of the Carmelite martyrs of Compiègne cherished by St. Thérèse at the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux.

July 17, 1897. Was St. Thérèse’s famous remark about her posthumous mission inspired by the Carmelites of Compiègne?

According to Last Conversations, on Saturday, July 17, 1897, Thérèse coughed up blood. Her sister Pauline, Mother Agnes of Jesus, writes that she said these words:

I feel that I'm about to enter into my rest. But I feel especially that my mission is about to begin, my mission of making God loved as I love Him, of giving my little way to souls. If God answers my desires, my heaven will be spent on earth until the end of the world. Yes, I want to spend my heaven in doing good on earth. This isn't impossible, since from the bosom of the beatific vision, the angels watch over us.

"I can't make heaven a feast of rejoicing; I can't rest as long as there are souls to be saved. But when the angel will have said: 'Time is no more!'" then I will take my rest; I'll be able to rejoice, because the number of the elect will be complete and because all will have entered into joy and repose. My heart beats with joy at this thought.[23][24]

An early version of Thérèse’s reported words was the “green notebook” prepared by her sister Pauline, Mother Agnes of Jesus. The typescript of the green notebook mentions, after the words quoted above, only Pauline’s notation “I observed that July 17 was the anniversary of the martyrdom of the Carmelites of Compiègne.” Bishop Gaucher asks:

Was it a coincidence that the announcement of Thérèse’s posthumous mission took place on the feast of her martyred sisters? Perhaps. But one can read here also the extraordinary fruitfulness of the hidden life, of the martyrdom of love to which Thérèse always aspired, of suffering offered for the salvation of the world.[25]

But there is more. Bishop Gaucher notes that the penciled lines on the handwritten “green notebook,” lines sadly erased in part, go beyond the typescript. The words “Sister Constance” and “novice” can still be seen. Sister Constance, born Marie-Genevieve Meunier, was the youngest of the martyrs. Shortly before she was eligible to make profession, the government passed a law forbidding the taking of religious vows, so, after six years in Carmel, she was still a novice. [Although Therese did profess her vows, she remained by request in the novitiate, as a "professed novice," all her religious life]. Sister Constance was the first to die, after having made her vows at the foot of the scaffold. It was she who, mounting the scaffold, suddenly began to chant Psalm 117, the psalm St. Teresa of Avila had chanted whenever she made a new foundation:

Praise the Lord, all ye nations!

Praise Him, all ye peoples!

For His mercy is confirmed upon us,

And the truth of the Lord endureth forever.

The other nuns intoned the psalm with Sister Constance, and the chanting of the psalm continued, voice after voice cut short, until the last nun was executed.[26]

Bishop Gaucher asks:

Isn’t it plausible that Thérèse had been struck by this novice, the first offered? She who remained in the novitiate her whole life, she who loved the young saints so well, did she not envy the fate of her young sister?[27]

June 6, 1905: The brief for the beatification of the martyred Carmelites of Compiègne and a petition for the opening of Thérèse’s cause

Pope Leo XIII, of whom Thérèse had begged permission to enter Carmel, declared the Carmelites of Compiègne venerable in 1902.[28]

Despite the immense popularity of St. Thérèse’s Story of a Soul, the Carmelites did not think of her canonization. But petitions arrived from many countries asking for her cause to be opened. Then, on June 6, 1905, Pope St. Pius X, who would soon call St. Thérèse “the greatest saint of modern times,” promulgated the brief of beatification for the martyred Carmelites of Compiègne.[29] On that same evening the Lisieux Carmel received a petition with 53 signatures from the seminary of Tournai in Belgium, asking them to introduce Thérèse’s cause. “The Carmelites could not help but see a sign in this coincidence. It seemed to them that the Carmelites of Compiègne were asking them to work for the glorification of their little sister.”[30]

St. Thérèse had always had a special love for many young martyrs: St. Agnes, St. Cecilia, St. Joan of Arc, Theophane Venard . . . In offering herself as a victim of holocaust to Merciful Love, she prayed to “become a martyr of Your Love, O my God!” She wrote that “the martyrdom of the heart is not less fruitful than the pouring out of one’s blood.” If the martyrs of Compiègne, who shed their blood for the faith, asked their sisters of Lisieux to work for the canonization of Thérèse, the martyr of love, might the Church one day recognize St. Thérèse of Lisieux as a martyr?

Update of July 16, 2022: For a detailed account of the process of equipollent canonization, which Pope Francis opened for these martyrs on February 22, 2022, please see "Famous nuns of 'Dialogue of the Carmelites' might soon be named saints," Aleteia, 3/3022. To read the full article, register for free as a member of Aleteia Premium.

To advance their canonization, we need to demonstrate the spread of their reputation for holiness and the favors received at their intercession. For details on where to e-mail your accounts of places where they are venerated and graces they have granted, please see Carmelite Quotes. That blog also furnishes the prayer for the canonization of the martyrs of Compiegne.

Further reading: To Quell the Terror: The True Story of the Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne, by William Bush. (Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, Inc., 1999).

Update of July 17, 2025: On December 18, 2024, Pope Francis formally canonized the Carmelite martyrs of Compiegne and extended their cult to the whole church through a process known as "equipollent canonization." For details, see "The Martyrs of Compiegne: Our Newest Saints" in the distinguished blog "Carmelite Quotes."

______________________________________________________________________________

[1] To Quell the Terror: The True Story of the Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne, by William Bush. (Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, Inc., 1999).

[2] Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, with thanks to the Internet Archive, accessed 7/17/16.

[3] Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, with thanks to the Internet Archive, accessed 7/17/16

[4] Catholiques de Compiègne - Carmel de Jonquières, accessed 7/18/16

4a. Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, with thanks to the Internet Archive, accessed 7/23/16

[5] Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, with thanks to the Internet Archive, accessed 7/18/16.

5a. St. Therese of Lisieux and the Influenza Pandemic of 1892, part 5: the subprioress, Sister Febronie of the Holy Childhood, on "Saint Therese of Lisieux: A Gateway," accessed 7/17/2021.

[6] Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, with thanks to the Internet Archive, accessed 7/18/16.

[7] Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, with thanks to the Internet Archive, accessed 7/16/16

[8] Documentation supplied by the Carmel of Compiegne, today at Jonquieres. Also: To Quell the Terror: The True Story of the Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne, by William Bush. (Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, Inc., 1999), seriatim.

[9] Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, with thanks to the Internet Archive, accessed 7/16/16

[10] Pierre Descouvement and Helmut-Nils Loose. Paris: Editions du Cerf [Orphelins Apprentis d’Auteuil – Office Central de Lisieux – Novalis], 1991, p. 341.

[11] Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, with thanks to the Internet Archive, accessed 7/16/16

[12] Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, with thanks to the Internet Archive, accessed 7/17/16

[13] Quoted and cited in Guy Gaucher, O.C.D., “Thérèse de Lisieux, des seize martyres de Compiègne, et Georges Bernanos,” Bulletin de la Société historique de Compiègne, Bulletin No. B34 (Les Carmelites de Compiègne), 1995, p. 146. With thanks to the Internet Archive. Accessed 7/17/16. My translation.

[14] Saint Thérèse of Lisieux: Her Life, Times, and Teaching, ed. Conrad De Meester, O.C.D., in chapter 14, “Thérèse’s Universal Influence,” by Pierre Descouvement and Raymond Zambelli, (Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, Inc., 1997), p. 259.

[14a]. On February 22, 2022, Pope Francis opened a special process known as "equipollent canonization" for them (Catholic News Agency).

[15] Storm of Glory, by John Beevers. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday Image Books, 1955, p. 118.

[16] Saint Thérèse of Lisieux: Her Life, Times, and Teaching, ed. Conrad De Meester, O.C.D., in chapter 14, “Thérèse’s Universal Influence,” by Pierre Descouvement and Raymond Zambelli, (Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, Inc., 1997), p. 256.

[17] Gaucher, “Thérèse de Lisieux, des seize martyres de Compiègne, et Georges Bernanos,” op. cit., p. 146, accessed 7/17/16.

[18] Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, accessed 7/17/16

[19] Letter of Mother Marie-Ange of the Child Jesus to Msgr. de Teil, 22 January 1909, quoted and cited in Sainte Thérèse de Lisieux (1873-1897) by Guy Gaucher, O.C.D. Paris: Editions du Cerf, 2010, p. 404. My translation.

[20] Sainte Thérèse de Lisieux: La vie en images, Pierre Descouvement and Helmut-Nils Loose. Paris: Editions du Cerf [Orphelins Apprentis d’Auteuil – Office Central de Lisieux – Novalis], 1991, p. 340.

[21] Catholiques de Compiègne - Carmel de Jonquières, accessed 7/17/16

[22] Sainte Thérèse de Lisieux: La vie en images, op. cit., pp. 338-339.

[23] St. Thérèse of Lisieux: Her Last Conversations, ed. John Clarke, O.C.D. Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, 1977, p. 102.

[24] Last Conversations (reported words of Thérèse) cannot be held on a level with Thérèse’s writings. But Thérèse’s letter of July 14, 1897 to her spiritual brother, Fr. Adolphe Roulland, expresses similar desires. Letters of Saint Therese of Lisieux, Vol. II (1890-1897), tr. John Clarke, O.C.D. Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, 1988, p. 1142.

[25] Guy Gaucher, O.C.D., ‘Thérèse de Lisieux, des seize martyres de Compiègne, et Georges Bernanos.” op. cit., p. 148, accessed 7/17/16. My translation.

[26] To Quell the Terror: The True Story of the Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne, op. cit., seriatim.

[27] Quoted and cited in Guy Gaucher, "Thérèse de Lisieux, des seize martyres de Compiègne, et Georges Bernanos,” op. cit., p. 149, accessed 7/17/16)

[28] The Martyrs of Compiegne, Faith ND (University of Notre Dame), accessed 7/17/2025.

[29] They would be beatified on May 27, 1906, the first recognized martyrs of the French revolution

[30] Saint Thérèse of Lisieux: Her Life, Times, and Teaching, op. cit., p. 258.

Copyright 2017-2025 by Maureen O'Riordan. All rights reserved.