Saint Therese of the Child Jesus

of the Holy Face

Day Three - "The Science of Divine Love," the Apostolic Letter declaring St. Therese of Lisieux a Doctor of the Church - Pope John Paul II comments on her "Story of a Soul" and other writings - October 13, 2017

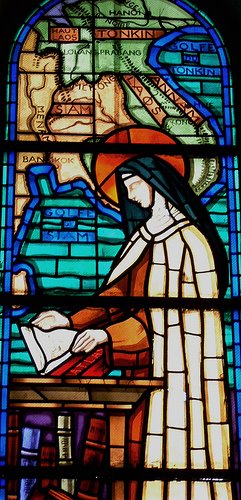

The writing-desk of St. Therese of Lisieux. Photo credit: Peter and Lliane Klostermann

6. Therese of the Child Jesus left us writings that deservedly qualify her as a teacher of the spiritual life. Her principal work remains the account of her life in three autobiographical manuscripts (Manuscrits autobiographiques A, B, C), first published with the soon to be famous title of Histoire d'une Ame (Story of a Soul).

In Manuscript A, written at the request of her sister Agnes of Jesus, then Prioress of the monastery, and given to her on 21 January 1896, Therese describes the stages of her religious experience: the early years of childhood, especially the time of her First Communion and Confirmation, adolescence, up to her entrance into Carmel and her first profession.

Manuscript B, written during her retreat that same year at the request of her sister Marie of the Sacred Heart, contains some of the most beautiful, best known and oft-quoted passages from the Saint of Lisieux. They reveal the Saint's full maturity as she speaks of her vocation in the Church, the Bride of Christ and Mother of souls.

Manuscript C, composed in June and the first days of July 1897, a few months before her death and dedicated to the Prioress, Marie de Gonzague, who had requested it, completes the recollections in Manuscript A on life in Carmel. These pages reveal the author's supernatural wisdom. Therese recounts some sublime experiences during this final period of her life. She devotes moving pages to her trial of faith: a grace of purification that immerses her in a long and painful dark night, illuminated by her trust in the merciful, fatherly love of God. Once again, and without repeating herself, Therese makes the light of the Gospel shine brightly. Here we find the most beautiful pages she devoted to trusting abandonment into God's hands, to unity between love of God and love of neighbor, to her missionary vocation in the Church.

In these three different manuscripts, which converge in a thematic unity and in a progressive description of her life and spiritual way, Therese has left us an original autobiography which is the story of her soul. It shows how in her life God has offered the world a precise message, indicating an evangelical way, the "little way", which everyone can take, because everyone is called to holiness.

In the 266 Letters we possess, addressed to family members, women religious and missionary "brothers", Therese shares her wisdom, developing a teaching that is actually a profound exercise in the spiritual direction of souls.

Her writings also include 54 Poesies (Poems), some of which have great theological and spiritual depth inspired by Sacred Scripture. Worthy of special mention are Vivre d'Amour!... (Poesies 17) and Pourquoi je t'aime, Marie! (Poesies 54), an original synthesis of the Virgin Mary's journey according to the Gospel. To this literary production should be added eight Recreations pieuses: poetic and theatrical compositions, conceived and performed by the Saint for her community on certain feast days, in accordance with the tradition of Carmel. Among those writings should be mentioned a series of 21 Prieres (Prayers). Nor can we forget the collection of all she said during the last months of her life. These sayings, of which there are several editions, known as the Novissima verba, have also been given the title Derniers Entretiens (Last Conversations).

excerpted from "Divini Amoris Scientia," the Apostolic Letter of Pope John Paul II declaring St. Therese of Lisieux a Doctor of the Church.

Day Two - Pope John Paul II recalls Therese's life and doctrine and considers her as a possible Doctor of the Church

Mosaic in the basilica at Lisieux: St. Therese with the first four Popes who paid tribute to her: Pius X, who introduced her cause; Benedict XV, who proclaimed her Venerable and praised the "way of spiritual childhood;" Pius XI, who named her patron of missions; and Pius XII, who declared her patron of France. Photo credit: Paul Ryan.

Mosaic in the basilica at Lisieux: St. Therese with the first four Popes who paid tribute to her: Pius X, who introduced her cause; Benedict XV, who proclaimed her Venerable and praised the "way of spiritual childhood;" Pius XI, who named her patron of missions; and Pius XII, who declared her patron of France. Photo credit: Paul Ryan.

3. The Pastors of the Church, beginning with my predecessors, the Supreme Pontiffs of this century, who held up her holiness as an example for all, also stressed that Thérèse is a teacher of the spiritual life with a doctrine both spiritual and profound, which she drew from the Gospel sources under the guidance of the divine Teacher and then imparted to her brothers and sisters in the Church with the greatest effectiveness (cf. Ms B, 2v-3).

This spiritual doctrine has been passed on to us primarily by her autobiography which, taken from three manuscripts she wrote in the last years of her life and published a year after her death with the title Histoire d'une âme (Lisieux 1898), has aroused an extraordinary interest down to our day. This autobiography, translated along with her other writings into about 50 languages, has made Thérèse known in every part of the world, even outside the Catholic Church. A century after her death, Thérèse of the Child Jesus continues to be recognized as one of the great masters of the spiritual life in our time.

4. It is not surprising then that the Apostolic See received many petitions to confer on her the title of Doctor of the Universal Church.

In recent years, especially with the happy occasion of the first centenary of her death close at hand, these requests became more and more numerous, including on the part of Episcopal Conferences; in addition, study conferences were held and numerous publications have pointed out how Thérèse of the Child Jesus possesses an extraordinary wisdom and with her doctrine helps so many men and women of every state in life to know and love Jesus Christ and his Gospel.

In the light of these facts, I decided carefully to study whether the Saint of Lisieux had the prerequisites for being awarded the title of Doctor of the Universal Church.

5. In this context I am pleased to recall briefly some events in the life of Thérèse of the Child Jesus. Born in Alençon, France, on 2 January 1873, she is baptized two days later in the Church of Notre Dame, receiving the name Marie-Françoise-Thérèse. Her parents are Louis Martin and Zélie Guérin, whose heroic virtues I recently recognized. After her mother's death on 28 August 1877, Thérèse moves with her whole family to the town of Lisieux where, surrounded by the affection of her father and sisters, she receives a formation both demanding and full of tenderness.

Towards the end of 1879 she receives the sacrament of Penance for the first time. On the day of Pentecost in 1883 she has the extraordinary grace of being healed from a serious illness through the intercession of Our Lady of Victories. Educated by the Benedictines of Lisieux, she receives First Communion on 8 May 1884, after an intense preparation crowned with an exceptional experience of the grace of intimate union with Jesus. A few weeks later, on 14 June of that same year, she receives the sacrament of Confirmation with a vivid awareness of what the gift of the Holy Spirit involves in her personal sharing in the grace of Pentecost. On Christmas Day of 1886 she has a profound spiritual experience that she describes as a "complete conversion". As a result, she overcomes the emotional weakness caused by the loss of her mother and begins "to run as a giant" on the way of perfection (cf. Ms A, 44v45v).

Thérèse wishes to embrace the contemplative life, like her sisters Pauline and Marie in the Carmel of Lisieux, but is prevented from doing so by her young age. During a pilgrimage to Italy, after visiting the Holy House of Loreto and places in the Eternal City, at an audience granted by the Pope to the faithful of the Diocese of Lisieux on 20 November 1887, she asks Leo XIII with filial boldness to be able to enter Carmel at the age of 15 years.

On 9 April 1888 she enters the Carmel of Lisieux, where she receives the habit of the Blessed Virgin's order on 10 January of the following year and makes her religious profession on 8 September 1890, the feast of the Birth of the Virgin Mary. At Carmel she undertakes the way of perfection marked out by the Mother Foundress, Teresa of Jesus, with genuine fervour and fidelity in fulfilling the various community tasks entrusted to her. Illumined by the Word of God, particularly tried by the illness of her beloved father, Louis Martin, who dies on 29 July 1894, Thérèse embarks on the way of holiness, insisting on the centrality of love. She discovers and imparts to the novices entrusted to her care the little way of spiritual childhood, by which she enters more and more deeply into the mystery of the Church and, drawn by the love of Christ, feels growing within her the apostolic and missionary vocation which spurs her to bring everyone with her to meet the divine Spouse.

On 9 June 1895, the feast of the Most Holy Trinity, she offers herself as a sacrificial victim to the merciful Love of God. On 3 April of the following year, on the night between Holy Thursday and Good Friday, she notices the first symptoms of the illness which will lead to her death. Thérèse welcomes it as a mysterious visitation of the divine Spouse. At the same time she undergoes a trial of faith which will last until her death. As her health deteriorates, she is moved to the infirmary on 8 July 1897. Her sisters and other religious collect her sayings, while her sufferings and trials, borne with patience, intensify to the moment of her death on the afternoon of 30 September 1897. "I am not dying; I am entering life", she had written to one of her spiritual brothers, Fr Bellière (Lettres 244). Her last words, "My God, I love you", are the seal of her life.

excerpted from "Divini Amoris Scientia," the Apostolic Letter of Pope John Paul II declaring St. Therese of Lisieux a Doctor of the Church.

"The Science of Divine Love" - Apostolic Letter Declaring St. Therese a Doctor of the Church - Day One - October 11, 2017

St. Therese with the map of Asia

St. Therese with the map of Asia

DIVINI AMORIS SCIENTIA

Apostolic Letter of Pope John Paul II

Proclaiming St. Therese a Doctor of the Church

October 19, 1997

To prepare for the 20th anniversary of Therese's doctorate on October 19, in nine days of preparation let's meditate on a different section of the Apostolic Letter each day.

1. THE SCIENCE OF DIVINE LOVE, which the Father of mercies pours out through Jesus Christ in the Holy Spirit, is a gift granted to the little and the humble so that they may know and proclaim the secrets of the kingdom, hidden from the learned and the wise; for this reason Jesus rejoiced in the Holy Spirit, praising the Father who graciously willed it so (cf. Lk 10:21-22; Mt 11:25-26).

Mother Church also rejoices in noting that throughout history the Lord has continued to reveal himself to the little and the humble, enabling his chosen ones, through the Spirit who "searches everything, even the depths of God" (1 Cor 2:10), to speak of the gifts "bestowed on us by God... in words not taught by human wisdom but taught by the Spirit, interpreting spiritual truths in spiritual language" (1 Cor 2:12,13). In this way the Holy Spirit guides the Church into the whole truth, endowing her with various gifts, adorning her with his fruits, rejuvenating her with the power of the Gospel and enabling her to discern the signs of the times in order to respond ever more fully to the will of God (cf, Lumen gentium, nn. 4, 12; Gaudium et spes, n. 4).

Shining brightly among the little ones to whom the secrets of the kingdom were revealed in a most special way is Therese of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face, a professed nun of the Order of Discalced Carmelites, the 100th anniversary of whose entry into the heavenly homeland occurs this year.

During her life Therese discovered "new lights, hidden and mysterious meanings" (Ms A, 83v) and received from the divine Teacher that "science of love" which she then expressed with particular originality in her writings (cf. Ms B, 1r). This science is the luminous expression of her knowledge of the mystery of the kingdom and of her personal experience of grace. It can be considered a special charism of Gospel wisdom which Therese, like other saints and teachers of faith, attained in prayer (cf. Ms C, 36r).

2. The reception given to the example of her life and Gospel teaching in our century was quick, universal and constant. As if in imitation of her precocious spiritual maturity, her holiness was recognized by the Church in the space of a few years. In fact, on 10 June 1914 Pius X signed the decree introducing her cause of beatification; on 14 August 1921 Benedict XV declared the heroic virtues of the Servant of God, giving an address for the occasion on the way of spiritual childhood; and Pius XI proclaimed her blessed on 29 April 1923. Shortly afterwards, on 17 May 1925, the same Pope canonized her before an immense crowd in St Peter's Basilica, highlighting the splendor of her virtues and the originality of her doctrine. Two years later, on 14 December 1927, in response to the petition of many missionary Bishops, he proclaimed her patron of the missions along with St. Francis Xavier.

Beginning with these acts of recognition, the spiritual radiance of Therese of the Child Jesus increased in the Church and spread throughout the world. Many institutes of consecrated life and ecclesial movements, especially in the young Churches, chose her as their patron and teacher, taking their inspiration from her spiritual doctrine. Her message, often summarized in the so-called "little way", which is nothing other that the Gospel way of holiness for all, was studied by theologians and experts in spirituality. Cathedrals, basilicas, shrines and churches throughout the world were built and dedicated to the Lord under the patronage of the Saint of Lisieux. The Catholic Church venerates her in the various Eastern and Western rites. Many of the faithful have been able to experience the power of her intercession. Many of those called to the priestly ministry or the consecrated life, especially in the missions and cloister, attribute the divine grace of their vocation to her intercession and example.

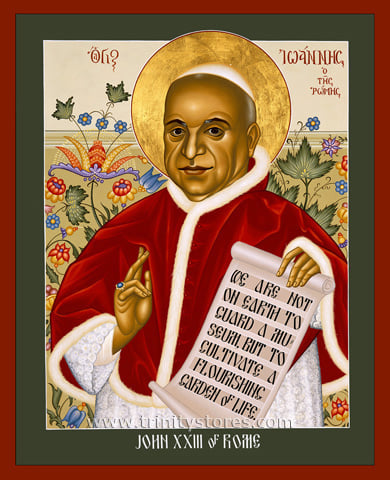

St. John XXIII's famous "moonlight speech" (October 11, 1962) on the night he opened the Second Vatican Council was inspired by St. Therese of Lisieux

Pope John XXIII by Br. Robert Lentz, OFM

"I didn't know what to say. I turned to my Teresina." - Pope John XXIII

On the night of October 11, 1962, Pope John XXIII gave the most popular and memorable papal speech of all time, known as his "moonlight speech." I discovered that, as he said privately that night, this famous off-the-cuff speech, which broke new ground in papal communications, was inspired by St. Therese of Lisieux. Gianni Gennari broke the story in his November 30, 2013 article "La storia 'vera' del Discorso papale piu celebre di tutti tempi" ("The true story of the most celebrated papal discourse of all times") for Vatican Insider (La stampa). This story appeared only in Italian, and I discovered it only while researching for the feast of St. John XXIII. I thank Vatican Insider for this valuable story.

On the night of October 11, 1962, thousands of people, many carrying torches, made their way to St. Peter's Square to celebrate the opening of the historic Second Vatican Council. Naturally, they hoped the Pope would speak to them.  Cardinal Capovilla. Photo credit: Salvador MirandaPope John's secretary, then-Monsignor and now Cardinal Loris Francesco Capovilla (alive and well at age 98 in 2014!), told Gennari that the Pope was at first reluctant to address the crowd. No doubt tired after this great day, Pope John said "I do not want to speak! I've already said everything this morning." But, seeing how many people were waiting with festive torchlights, Pope John relented, asked for his stole, and came to the window (then already "the Pope's window," and now the place from which the Pope delivers his Angelus message on Sundays).

Cardinal Capovilla. Photo credit: Salvador MirandaPope John's secretary, then-Monsignor and now Cardinal Loris Francesco Capovilla (alive and well at age 98 in 2014!), told Gennari that the Pope was at first reluctant to address the crowd. No doubt tired after this great day, Pope John said "I do not want to speak! I've already said everything this morning." But, seeing how many people were waiting with festive torchlights, Pope John relented, asked for his stole, and came to the window (then already "the Pope's window," and now the place from which the Pope delivers his Angelus message on Sundays).

First, please watch "The speech of a lifetime," a brief two-minute reflection in English on this historic night.

Now, to see this memorable torchlit night in Rome and hear the Pope's words, watch this beautiful two-minute film:

His impromptu remarks are called "the moonlight speech" because he said:

Here all the world is represented. One might even say that the moon rushed here this evening – Look at her high up there – to behold this spectacle.

You can hear in the video how the people began to laugh and applaud as soon as he mentioned the moon. Among his most famous words:

When you go back home, you will find your children: and give them a hug and say,“This is a hug from the Pope.

What a departure from the formal Papal words of the past!

Pope John's secretary now tells us that these words were inspired directly by St. Therese of Lisieux.

After speaking, and seeing and hearing the enthusiasm of the people in the square who were captivated by his enchanting words, the Pope came in. Taking off his stole, he gave it to Monsignor Capovilla and said in these exact words: "I did not know what to say. I turned to my Teresina [my "little Therese"]. Behold, the help of St. Therese of Lisieux was the origin of this stroke of true imagination, of 'creative' and communicative genius which, in fact, is considered the most famous and popular papal speech of all time.

[my translation from "The true story of the most celebrated papal discourse of all times") for Vatican Insider (La stampa)].

How Therese's love for the people and for children shone out in the words she inspired in Pope John! Read the full text of this short "speech on the moon" at the Web site A-mused. Note also Pope Benedict's words in 2012 on the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council when he recalled that night:

"Fifty years ago on this day I too was in this square, gazing towards this window where the good Pope, Blessed Pope John looked out and spoke unforgettable words to us, words that were full of poetry and goodness, words that came from his heart."

from Salt and Light Media.

Finally, see this April 27, 2016 story from Vatican Radio, which contains a link to a radio show which interviews those who heard this historic speech and some who knew Pope John. At that radio show you can also hear Pope John's valiant attempt to welcome pilgrims in English. [I am sorry; the linked page has disappeared from the Web).

May St. Therese, who inspired Pope John with these "unforgettable words," continue to inspire Pope Francis and all of us.

"Therese of Lisieux the Woman, Doctor of the Church" - October 10, 2017

Statue of St. Therese, St. Pierre's Cathedral, Lisieux

Statue of St. Therese, St. Pierre's Cathedral, Lisieux

Thérèse of Lisieux the Woman, Doctor of the Church

29. The experience and doctrine of Thérèse of Lisieux gain special significance in our day when new horizons are opening up for the presence and action of women in society and in the Church. Women are called to be "signs of God's tender love towards the human race,"and to enrich humanity with their "feminine genius."25 The young Carmelite of Lisieux accomplished both things in her life. We can see this clearly in her writings.

Thérèse of the Child Jesus transmits her spiritual experience with an engaging feminine style that is direct and intimate. Despite the expectations of her times, she manifested her Gospel conviction on the equality of men and women and the importance of mutual collaboration as disciples of Jesus. We can see this especially in her letters to her missionary brothers with whom she shares her human and spiritual experiences. She does not hesitate to express her point of view on theological issues and Christian experience. She writes about her concept of God's justice, the way of spiritual childhood, and trust in divine mercy.

30. Her femininity, like that of Teresa of Jesus, resulted in greater commitment to the Gospel and to overcoming all the prejudices that emarginated women of her times. Thérèse of Lisieux knew from experience what it was to be a woman in society and in the church at the end of the 18th century. In manuscript A, she tells us clearly and humorously what she felt during her trip to Rome before entering Carmel:

I still cannot understand why women are so easily excommunicated in Italy, for every minute someone was saying: "Don't enter here. Don't enter there, you will be excommunicated!" Ah! poor women, how they are misunderstood! And yet they love God in much larger numbers than men do; and during the Passion of Our Lord, women had more courage than the apostles since they braved the insults of the soldiers and dared to dry the adorable Face of Jesus.26

Her womanhood, which she expressed with the freshness and sincerity of a free person, led her to a reflection on the Gospel: the emargination of women makes them participate more closely in the mystery of Christ who was despised at his passion. "It is undoubtedly because of this that He allows misunderstanding to be their lot on earth, since he chose it for himself. …In heaven, He will show that His thoughts are not men's thoughts, for then the last will be first."27 Jesus made women the first witnesses of his resurrection.

31. Today as areas for greater participation in society and church open up for women, they can find encouragement in Thérèse of Lisieux to live as John Paul II said, " a culture of equality between men and women." Again Hans Urs von Baltahasar noted, on the occasion of the celebrations for centenary of Thérèse of Lisieux's birth, that she opened the whole field of theology to feminine reflection: "The theology of women has never been taken seriously nor integrated by the establishment. However, after the message of Lisieux, it must finally consider it in the present reconstruction of Dogmatic Theology."28

This corresponds to what the postsynodal document Vita Consecrata presents as new perspectives for women in the Church: "In the field of theological, cultural, and spiritual studies, much can be expected from the genius of women, not only in relation to specific aspects of feminine consecrated life, but also in understanding the faith in all its expressions."29

Conclusion

32. God surprises us anew with this sister of ours. In her he breaks so many patterns of human logic in a way that calls attention to his own gratuitous initiative in choosing those he wants. God seeks to realize his works and manifest the greatness of his power and action in those who open themselves confidently to his merciful love as they accomplish his will.

With the proclamation of the doctorate of St. Thérèse, the Lord confirms what the Old Testament states and the New Testament restates in its fullness: that God communicates himself to the simple, giving them his wisdom and revealing to them the secrets of his life and workings throughout history. In effect, as the book of Wisdom told at the threshold of Christ's coming: "Length of days is not what makes age honorable, nor number of years the true measure of life; understanding, this is grey hairs; untarnished life, this is ripe old age. Having won God's favor, he has been loved. …Having come to perfection so soon, he has lived long" (Wis 4:8-10, 13). In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus, full of joy in the Holy Spirit, proclaims a divine logic so very different from ours: "I bless you, Father, Lord of heaven and of earth, for hiding these things from the learned and the clever and revealing them to little children. Yes, Father, for that is what it has pleased you to do" (Lk 10:21-22).

33. The Lord, Father of all light, from whom comes all that is good, all that is perfect (cf. Jm 1:17), has given Carmel yet another gift with Thérèse of Lisieux's doctorate. It is a free gift that demands a response of love and generous commitment to our vocation and mission in the Church and in the world. May our sister Thérèse of Lisieux obtain for us from the Lord the grace to be his collaborators in bearing witness and proclaiming the good news to our brothers and sisters of the third millennium. May we be authentic followers of Jesus, in communion with Mary, the first one to receive the joyful news of salvation and who proclaimed it with the joy of one who has discovered that God gives himself freely to the poor, humble, and simple.

Rome, 1 October, 1997

- excerpted from Therese, A Doctor for the Third Millennium, the joint pastoral letter written by the Carmelite superiors general, Fr. Camilo Maccise, O.C.D. and Fr. Joseph Chalmers, O. Carm., when Therese was named a doctor in 1997. For the footnotes, please follow the link to the complete document.