Saint Therese of the Child Jesus

of the Holy Face

The 130th anniversary of the religious profession of St. Therese of Lisieux on September 8, 1890

To relive St. Therese's profession with her in word and image, please see my article "The religious profession of St. Therese, September 8, 1890." Thank you.

125 years ago with St. Therese: Therese writes the poem "To my dear Mother, the Fair Angel of my Childhood" - September 7, 1895

September 7, 1895 was the 34th birthday of Therese's sister Pauline, Mother Agnes of Jesus. As a gift for her sister's birthday, Therese wrote "To my dear Mother, the Fair Angel of my Childhood."

Detail from Jacopo di Cione, "Six Angels," Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Detail from Jacopo di Cione, "Six Angels," Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City  Detail from Jacopo di Cione, "Six Angels," Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Detail from Jacopo di Cione, "Six Angels," Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Mother Agnes had been serving as prioress for two and a half years, years of grace for Therese, who wrote that on the day of her election "Pauline became my living Jesus." The tenderness and gratitude that overflow in this poem were undoubtedly evoked by the fact that since January 1895 Therese had been writing her childhood memoir, a long letter to Pauline, which brought vividly before her Pauline's delicate and vital role in her life.

Therese depicts herself as a child and Pauline as the angel "who guides my steps," assigning to her sister the role of guardian angel. This angel sang of "the charms of Jesus," "the joy of a pure heart," the "beautiful blue Heaven," "the God of childhood" (a phrase that appears only here in Therese's writing), "the Virgin Mary." Tactfully Therese alludes only with the word "alas!" to the acute distress Pauline's departure for Carmel caused her, and dwells instead on her present happiness:

125 years ago with St. Therese: her cousin Marie Guerin enters Carmel. For her Therese writes "Canticle of a Soul Having Found the Place of its Rest," Poem 21

St. Teresa of Avila praying before an image of Christ captive. (Licensed from Shutterstock Images)

St. Teresa of Avila praying before an image of Christ captive. (Licensed from Shutterstock Images)

On August 15, 1895, the feast of the Assumption (which was her personal feast-day), Therese's cousin Marie Guerin entered the Carmel of Lisieux. Marie, at 25 a little less than three years older than Therese, was the younger daughter of Isidore Guerin, the brother of Therese's mother, St. Zelie, and his wife, Celine. Marie was lively, witty, affectionate, sensitive, and gifted with a beautiful soprano voice.

The feast of the Assumption

Even before her entrance, Marie had kept the feast of the Assumption as her personal feast-day (what is now sometimes called a "name day"). Before Celine's entrance in 1894, Marie had posed for Celine, who took a photograph of Marie to serve as a model for a painting of the Assumption Celine painted for the chapel of the Benedictines at Bayeux. (if you click on the link to the photograph on the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux, you will find a link to Celine's resulting painting).

Madame Guerin had written Pauline, who was then prioress, asking deferentially that Marie's entrance might be set for her feast, August 15. Marie's mother and father, both fervent Catholics, found her vocation a privilege, but they were deeply saddened by losing her. Their older daughter, Jeanne, had married five years before and moved to Caen with her husband, and Marie's entrance left them bereft.

Therese as assistant novice mistress

From the time of Pauline's election as prioress in 1893, she confided privately to Therese the formation of the novices (Martha of Jesus, Marie-Madeleine of the Blessed Sacrament, Marie of the Trinity, Genevieve of St. Therese (her sister Celine), and now Marie Guerin, who took the name Marie of the Eucharist). Mother Gonzague held the title of novice mistress; Therese was dubbed "senior novice" and assigned merely to help her, but Pauline said later that she was, in fact, depending on Therese to form all the novices. Marie Guerin, the last to enter during Therese's lifetime, brought the number of novices to five: an injection of youth and energy to the community.

Therese's poem "Canticle of a Soul Having Found the Place of Its Rest"

It was the custom for the new postulant to sing something for the community at evening recreation on the day of her entrance. To showcase her cousin's lovely voice, Therese composed the poem "Canticle of a Soul Having Found the Place of Its Rest." As usual, she wrote with sensitivity to the person and the occasion, but also expressed her own desires:

O Jesus! on this day. you have fulfilled all my desires.

From now on, near the Eucharist, I shall be able

To sacrifice myself in silence, to wait for Heaven in peace.

Keeping myself open to the rays of the divine Host,

In this furnace of love, I shall be consumed,

And like a seraphim, Lord, I shall love you.*

Sister Therese of St. Augustine left us testimony about what Therese meant by "loving like a seraph" in the "furnace of love." At the 1910 Process, she testified:

In Sister Therese, the love of God dominated everything else; her dream was to die of love. But then she would add: "To die of love, we must live by love." So she strove to develop this love day by day, because she wanted it to be of the highest quality. Her ambition was to love like a seraph, to be consumed by the devouring flames of pure love without feeling them, so that her self-sacrifice would be as complete as possible.**

"Living on Love!," Therese's poem from February 1895

In this "Canticle," Therese sets forth some elements of a programme of life for her cousin. But on the same day she left on Marie's bed in her new cell, the manuscript surrounded by flowers. a copy of her earlier poem "Living on Love!," written during the Forty Hours Devotion in February 1895. This composition sets forth a far more powerful and detailed spiritual itinerary, rooted in the gospels and unlimited in scope. Celine called it "the king" of Therese's poems. The editors write of "the solemn fervor of this love poem," and its 15 stanzas are inexhaustible. Here I quote only stanza five:

Living on Love is giving without limit

Without claiming any wages here below.

Ah! I give without counting, truly sure

That when one loves, one does not keep count!...

Overflowing with tenderness, I have given everything,

To His Divine Heart..... lightly I run.

I have nothing left but my only wealth:

Living on Love.***

1895: a year of grace for Therese

Marie's entrance enhanced the richness of the year 1895, the year of "the Mercies of the Lord" for Therese. In 1894 she had been delivered from her father's long trial and now felt his closeness. Then her deep desire of having Celine, her inseparable companion, join her in Carmel had been fulfilled. After her rich play "Joan of Arc Accomplishing Her Mission," she had, at the request of Pauline, her prioress, begun to review her life and write her "thoughts on the graces God has granted" to her. This review brought the graces of the past vividly before her. In February Celine received the Habit, and her father's virtues were evoked in the sermon on that occasion. Later in February Therese was inspired to write her great poem "Living on Love." On June 9 she received the great grace of being inspired to offer herself, with Celine, to the Merciful Love of God. During the summer she persuaded her oldest sister, Marie, to offer herself as well. Now her cousin was coming to fulfill her vocation.

In the community context, the Martin sisters were rather prominent at this time. The community had elected Pauline, Mother Agnes of Jesus, prioress in 1893, at the early age of 31. This was a great grace for Therese. Their oldest sister, Marie of the Sacred Heart, was "provisoire" (in charge of procuring food for the community). Therese was charged with helping to form the novices, and her poems and religious plays were beginning to make her a little more known among some of the nuns. Only a few suspected the fire of love burning in her heart.

_________________________

* "The Poetry of Saint Therese of Lisieux," tr. Donald Kinney, O.C.D. (Washington, D.C.: Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, 1996), p. 112.

** "St. Therese of Lisieux by Those Who Knew Her," ed. and tr. Christopher O'Mahony, O.C.D. (Dublin: Veritas Press, 1973, p. 193.

*** The Poetry of Saint Therese of Lisieux, op. cit., p. 90.

125 years ago with St. Therese: She writes poem 20, "My Heaven on Earth," for Sister Marie of the Trinity's 21st birthday, August 12, 1895

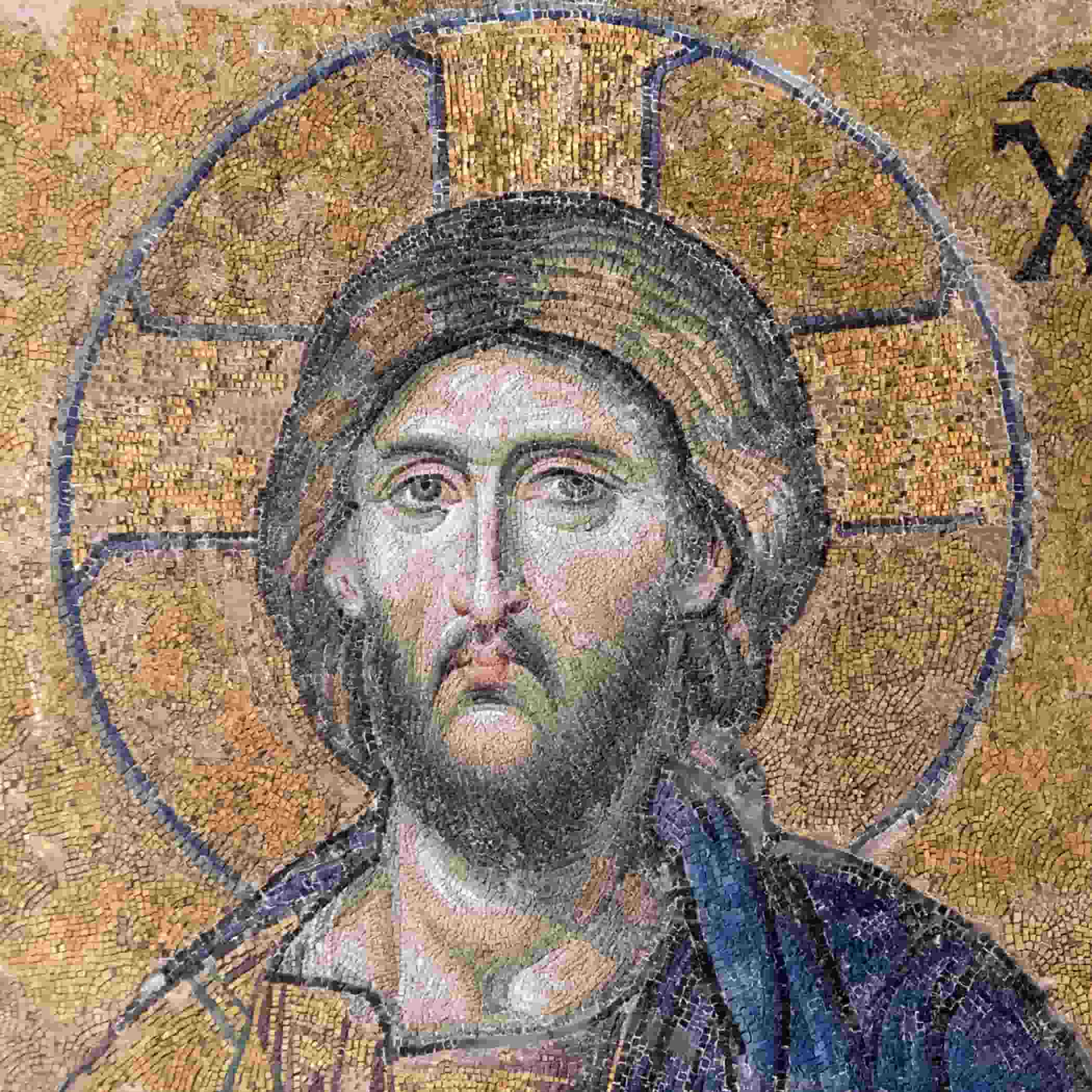

Icon of the Face of Jesus. (Licensed from Shutterstock).

Icon of the Face of Jesus. (Licensed from Shutterstock).

"My Heaven on Earth"

Jesus, your ineffable imageIs the star that guides my steps.Ah! you know, your sweet FaceIs for me Heaven on earth. . . .Your Face is my only Homeland.It's my Kingdom of Love.

125 Years Ago with St. Therese: her poem "The Atom of Jesus-Host," summer 1895

It was probably in the summer of 1895 that Therese wrote the poem "The Atom of Jesus-Host" at the request of Sister St. Vincent de Paul, a lay-sister who was evidently not enthusiastic about the monastery's receiving members of the rising bourgeoisie like the Martin sisters.

Sister St. Vincent de Paul was remarkably devoted to the Eucharist, and she gave Therese her thoughts about herself as the "atom" of Jesus and asked for a poem on that theme. The energy hidden in the atom had not yet been discovered; to Sister St. Vincent the word meant simply a tiny fleck of dust.*

When Sister St. Vincent de Paul entered the Carmel, she was distressed to discover that the grille between the choir and the sanctuary was covered with black cloth so that the nuns could not even see the tabernacle. So great was her desire to be as near the Eucharist as possible that she used to spend the whole hour set aside for "mental prayer" in the evening before supper hidden in the corner of the choir closest to the little Communion grille. This was one of the darkest corners of the choir, but was closest to the tabernacle on the other side of the grille.

The editors of The Poetry of Saint Therese of Lisieux describe this as "second-rate poetry that we will quickly pass over." They are not mistaken, for, when she writes according to a unique inspiration, Therese's poems are more spontaneously written and more deeply felt than when she writes to order. But this poem is of biographical interest because Therese wrote it for Sister St. Vincent de Paul, about whom her sister Pauline, Mother Agnes of Jesus, said "[Therese] told me she had to overcome more antipathy for Sister St. Vincent de Paul (who was very smart) than for poor Sister Marie of St. Joseph (a mentally ill sister whom Therese helped in the linen room in 1896-1897). "1 Yet Therese wrote four poems for this Sister, and they are not devoid of Therese's own sentiments about the Eucharist.

Sister St. Vincent de Paul and St. Therese

Zoe Alaterre of Cherbourg, orphaned at age eight, grew up at the orphanage operated by the Sisters of St. Vincent de Paul in Caen, where Leonie and Celine had boarded in the spring of 1889 to be near their father at the Bon Sauveur Hospital. Entering at age 22, she was saddened that in Carmel she could no longer receive Communion every day. She was talkative, had opinions about everything, and was called the "living encyclopedia." Very courageous in suffering, she worked hard despite being chronically ill throughout her religious life. Read about the phases of Sister St. Vincent de Paul's complicated relationship with St. Therese in her biography on the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux. And read the brief and somewhat humorous obituary circular Therese's sister Pauline, Mother Agnes of Jesus, wrote when Sister St. Vincent de Paul died in 1905.

i thank the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux for digitizing and sharing the documents that permit us to know Sister St. Vincent de Paul.

______________

* The Poetry of St. Therese of Lisieux, tr. Donald Kinney, O.C.D. (Washington, D.C.: Washingotn Ptovince of Discalced Carmelites, 1996), p. 106.

1. Biography of Sister St. Vincent de Paul on the Web site of the Archives of the Carmel of Lisieux at http://archives-carmel-lisieux.fr/english/carmel/index.php/les-soeurs-dexperience/st-vincent-de-paul/biographie, accessed 8/5/2020.